The following writers contributed to this story for Rural Health Quarterly: Dr. Sanjeev Arora, Karla Thornton, Miriam Komaromy, Bruce Struminger, Joanna Katzman, Matt Bouchonville, Mike Lewicki and Jennifer Snead.

[dropcap]F[/dropcap]or almost three years, Type 1 diabetes controlled Kaycee May’s life. May, who lives in Portales, a town of about 12,000 in eastern New Mexico, received her diagnosis when she was 17. Her condition was so serious that her doctors feared she would fall into a diabetic coma. They sent her to a hospital more than 100 miles away in Lubbock, Texas, where she stayed for a week.

Afterward, she travelled to Lubbock every month to see the specialist who managed her care—a two-hour drive each way for a 30-minute appointment.

These days, May controls her diabetes, instead of the other way around. Through a program called Endo ECHO, she now gets excellent care for her diabetes right in Portales, where she lives and works.

“Before Endo ECHO, I felt like I had a gigantic burden,” says May, who, in addition to being a wife and mother, works at a daycare center and goes to college. Now, she says, her life is much more manageable.

May’s situation is typical for millions of Americans who live in rural and remote communities where specialist doctors are few and far between. People who have common but complex health conditions may have to travel hundreds of miles and wait weeks or months to get the care they need. That often means taking a day off from school or work, paying for gas or a bus ticket—or going without care until the condition becomes much more serious and more difficult and costly to treat.

It’s no wonder we are seeing increasing health gaps between Americans living in rural areas and those in urban areas. A report from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that, compared to urban dwellers, people in rural communities have higher death rates and suffer more preventable deaths from heart disease, stroke, cancer, injury, and chronic respiratory disease.

Endo ECHO, the program that turned Kaycee May’s life around, is part of Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes), which helps people in rural and remote communities across the United States get high-quality health care for more than 50 common complex medical conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis, chronic pain, heart disease, HIV, hepatitis C, and opioid addiction.

RELATED STORY: An Introduction to Project ECHO

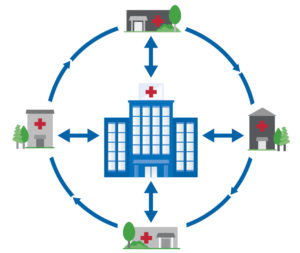

Project ECHO educates and supports community providers—including not only primary care physicians but also nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, counselors, social workers and community health workers—so that they can provide specialized care and services for their patients, in their communities.

[dropcap]H[/dropcap]ere’s how it works:

Primary care providers who join Project ECHO choose a common, complex health problem, such as HIV or chronic pain, in which they want to specialize. These providers enroll in ECHO free of charge, usually with one or more colleagues, at a community health center or federally qualified health center. Through basic videoconferencing technology, they participate in weekly teleECHO clinic sessions, sort of like virtual grand rounds, led by a team of specialists located hundreds—or even thousands—of miles away.

Primary care providers who join Project ECHO choose a common, complex health problem, such as HIV or chronic pain, in which they want to specialize. These providers enroll in ECHO free of charge, usually with one or more colleagues, at a community health center or federally qualified health center. Through basic videoconferencing technology, they participate in weekly teleECHO clinic sessions, sort of like virtual grand rounds, led by a team of specialists located hundreds—or even thousands—of miles away.

The specialist team includes people from all the professions needed to treat the condition at hand. For example, the Endo ECHO team at the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center (UNMHSC) in Albuquerque that supports May’s primary care provider in Portales has an adult endocrinologist, a pediatric endocrinologist, a nephrologist, a pharmacist, a psychiatrist, a nurse manager, a community health worker and a social worker. This way, community providers seeking specialty knowledge gain access to a range of perspectives and expertise together, in real time.

The teleECHO sessions involve primary care providers at multiple sites. For example, every Wednesday at noon, teams of primary care providers from nine community health centers across New Mexico connect to the Endo ECHO clinic session. During the two-hour sessions, providers take turns presenting de-identified patient cases and working with specialists to determine treatment.

The specialists listen, ask questions, and offer their advice. They are also available to primary care providers for guidance on cases outside the clinic sessions. Although these specialists never see the patients whose cases they’re discussing, they provide expert advice to the trained clinicians who know the patients best, in this way helping to ensure that these patients receive excellent, comprehensive care in their own communities.

Through Project ECHO, community health providers acquire the knowledge, skills, and support they need to provide high-quality care to patients who otherwise might not be able to get it. They can do more for more patients. By maintaining treatment in local communities, that care is more efficient and more patient-centered.

And by sharing their expertise and working with multi-disciplinary teams to support primary care providers in rural and underserved areas, specialists help more patients get the care they need to live healthier lives. Their knowledge and expertise reach exponentially more patients than when they see patients one on one.

[dropcap]P[/dropcap]roject ECHO started in New Mexico, where 32 of 33 counties are fully or partly in federally designated health professional shortage areas.

Originally, we sought a way to bring life-saving treatment to the more than 28,000 New Mexicans infected with hepatitis C. In 2004, fewer than 5 percent of those patients had been treated.

The liver disease clinic at UNMHSC was one of only two such clinics in the state at the time where patients with hepatitis C could get treatment—and it had an eight-month waiting list. Knowing that thousands of patients were suffering and even dying from a curable disease because they couldn’t access treatment was unacceptable to us.

Accordingly, Project ECHO at UNMHSC was launched and developed a partnership with the state health department, the Indian Health Service, the state prisons (which housed 2,300 infected and untreated inmates), and community clinicians who were willing to treat hepatitis C in rural areas.

An evaluation of Project ECHO published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2011 found that the outcomes of hepatitis C patients treated by primary care providers trained through Project ECHO were equal to those of patients treated by university specialists. And many more people were getting treatment for hepatitis C as a result of Project ECHO—thousands more.

Since then, Project ECHO has expanded far beyond New Mexico’s borders, serving residents of rural and remote communities across the United States and in Africa, Asia, Europe, and Central and South America.

The model has demonstrated remarkable flexibility—it works across geographic regions, across cultures, and across payment systems. In health care, it is being used to spread best practices for problems as diverse as autism, cancer, bone health, mental illness, and reproductive health. Other systems, including education and law enforcement, are

exploring the ECHO model as well.

Currently, ECHO is significantly expanding its effort to combat America’s opioid addiction crisis. This evolved out of work to address New Mexico’s terrible and longstanding problems with opioids. For example, Española, a town in the north-central part of the state with fewer than 11,000 residents, has consistently ranked among the top U.S. cities for per-capita rates of opioid overdose deaths.

Until just a few years ago, treatment for opioid addiction was virtually non-existent in Española. Today, hundreds of patients are in treatment. Lives are being saved – and changed.

“There’s more hope in the community,” says Leslie Hayes, M.D., a primary care physician at Española’s El Centro Family Health Clinic. Hayes is one of three physicians in Española certified to prescribe buprenorphine for opioid addiction. All three were trained to prescribe buprenorphine through Project ECHO; Hayes was the first. She typically carries the maximum allowable caseload for buprenorphine treatment—100 patients, many of whom are pregnant women.

Now, Hayes not only provides opioid addiction treatment—through Project ECHO, she has become an expert, serving as a mentor to physicians around the Southwest who are trying to provide care for pregnant women undergoing buprenorphine treatment. In her own practice, she ensures that women get proper prenatal care and monitors their progress after birth. Some of these women now have toddlers who are healthy and doing well.

Last year, the White House presented Leslie Hayes with an award in recognition of her work as a Champion of Change in her community.

Now the effort that began in New Mexico is taken to a national level, through work with the U.S. Health Resources Services Administration (HRSA) and in partnership with the University of Washington, the Billings (Mont.) Clinic, Huther Doyle and the Western New York Collaborative, and the Boston Medical Center. Together, we are training primary care providers at more than 110 federally funded health centers to treat substance use disorders, including opioid addiction with buprenorphine. In addition, through federal funding provided under the 21st Century Cures Act, 20 states are using the ECHO model to combat opioid addiction.

Opioid ECHO, as the new HRSA program is called, aims to dramatically increase treatment capacity for substance use disorders in underserved communities where the need for treatment may be great but the availability of effective care is limited. Essentially, we are trying to create many more Leslie Hayes’s across the country.

Mental and behavioral health is another area where we are working hard to increase treatment capacity in rural communities. It’s estimated that up to 80 percent of mental health disorders go undiagnosed and therefore untreated. This is a huge problem in rural America, where, again, there simply aren’t enough specialist providers to meet the need.

In many rural communities, the nurse practitioners and other non-physician clinicians who provide the bulk of primary care are also the ones practitioners’ patients turn to when they have mental and behavioral health problems. Typically, however, these clinicians lack the training, support, and confidence to provide high-quality care for these disorders.

For three years, Project ECHO has tested a new model that provides additional training and practice experience in mental and behavioral health treatment to family nurse practitioners working in community health centers. These family nurse practitioners partner with community health workers who have also received specialized training and practice experience. Together, they form a primary behavioral health care team based in the community, in a setting that patients already know and trust.

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]s stories like Kaycee May’s and Leslies Hayes’s show, Project ECHO has the potential to change the dynamic of health care across rural America. Rural communities have critical assets that frequently are overlooked: the dedicated primary care physicians, nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, community health workers, counselors and social workers who are the backbone of rural health care. By engaging these front-line providers in a learning network where they receive ongoing mentorship and support, the ECHO model builds permanent local capacity to provide specialized care.

In addition, providers who participate in Project ECHO experience increased professional satisfaction and reduced feelings of professional isolation. This is critical in rural communities, where provider burnout and stress are high. We want providers to feel satisfied with and supported in their work, and we want them to continue practicing in rural communities. Project ECHO can help.

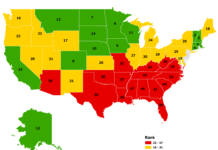

The future is promising. Currently, Project ECHO has teleECHO clinics in 30-plus states and more than 130 centers of excellence, usually universities or academic medical centers, that we call “hubs.” Although the model has spread quickly, we believe that pace will pick up even more. In December 2016, following unanimous approval by Congress, the ECHO Act was signed into law. The ECHO Act directs the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and HRSA to study the ECHO model and its ability to improve patient care and provider education, and to report those findings to Congress, along with recommendations for reducing barriers to use and supporting opportunities for further adoption of the model. Congressional leaders on both sides of the political aisle expressed deep optimism to help patients in rural areas get the care they need, when they need it.

Project ECHO’s roots are in rural America. And although we have set a goal to touch 1 billion lives worldwide by the year 2025, we envision that millions of those lives will be in small towns, tribal villages, and remote communities across the United States.