[dropcap]E[/dropcap]arly in the afternoon on a temperate June day, Rodrigo Gallego drove along the mildly undulating roads of the Black Dirt Region of Orange County, New York, where, he estimated, more than 500 migrants from Puebla, Mexico work the fields of the surrounding onion farms.

Originally from Columbia and fluent in Spanish, Gallego, 53, is a community health worker at the nearby HRHCare Alamo Health Center. He spends Monday through Friday steering the clinic’s van through the entrance of one farm after another, stopping to speak with the workers who wave him down.

Gallego connects them to health care, taking them to the Alamo clinic and regional specialists, translating and keeping in regular touch. Their primary complaints are vision problems, fingernail fungus, skin rashes and back pain, he said. Most speak no English, and many have no way of getting around.

“Some people say to me, ‘Oh, you’re just a driver.’ But I say I am a person who listens to what these workers need,” said Gallego, remembering his own struggles as a newly arrived immigrant in 1986.

Last year over the course of three days, he helped a migrant farmworker with a lump in her breast make an appointment at the clinic, accompanied her to see a surgeon at the Catskill Regional Medical Center and helped her apply for the hospital’s charity care.

Gallego pulled up to a house trailer where a worker on his lunch break was standing by the door. Gallego had taken the man to the Alamo clinic a few weeks earlier. Now he needed Gallego’s help with the resulting laboratory bill for blood work. The amount seemed too high, and Gallego took the paperwork and said he would investigate.

“My job is not limited to health,” said Gallego, who has held his position with HRHCare Community Health, a nonprofit system of Federally Qualified Health Centers serving the Hudson Valley and Long Island, for 15 years. “Sometimes they need help sorting through bills. Sometimes they need clothes. Sometimes they need food.”

Community health workers have been around for decades, helping underserved communities address the negative effects of so-called social determinants of health, such as language barriers, unstable housing, substandard education, environmental perils and limited access to transportation and to healthy foods.

“These are special people who relate to the population that they serve,” said Ann

Kauffman Nolon, president and chief executive officer of HRHCare Community Health, which has employed community health workers since its first health center opened in Peekskill, New York in 1975.

And they are in increasing demand, in part because the federal government began awarding grants under the 2010 Affordable Care Act to hire them. In 2016, there were roughly 52,000 community health workers in the United States, up from about 38,000 four years earlier, a 37 percent increase, according to the U.S. Department of Labor.

Experts in the field say those absolute numbers don’t capture the tens of thousands who volunteer or are in temporary positions that are funded by grants as well as thousands of others who do the same work under an array of titles.

But as demand for their services rise, many community health workers are finding that the nature of their job is changing.

“My job is not limited to health. Sometimes they need help sorting through bills.

Sometimes they need clothes. Sometimes they need food.”

Public health departments, schools, community-based social service organizations, religious organizations and Federally Qualified Health Centers are the traditional users of community health workers. Now as hospitals and health plans face steady government pressure to lower costs and improve health outcomes, they too are turning to community health workers to help them reach those goals. In fact, the number of community health workers employed by hospitals climbed by 74 percent between 2012 and 2016, according to government figures.

The prospect of working for large health care institutions makes some community health workers uneasy. They worry that they’ll be turned into nursing assistants and be asked to take blood pressures or be told to sit at a desk all day helping patients fill out forms rather than visiting people at home and in their neighborhoods.

To protect their mission, gain professional respect and promote more reliable pay, community health workers in some states are urging their legislatures to adopt a certification program. But certification is controversial. Opponents say it’s unnecessary and harmful because the requirements can bar effective people from the field.

BECOMING PART OF THE HEALTHCARE TEAM

Molina Healthcare operates health plans in California, Florida, Illinois, Michigan, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, South Carolina, Texas, Utah, Washington, Wisconsin and Puerto Rico. The company contracts with local health departments to administer government programs, such as Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program, and with the federal government to administer Medicare. It employs about 300 community health workers across ten different plans.

Molina hired its first community health workers in 2012, after a successful pilot study in New Mexico. In that study, hundreds of plan members with poorly controlled chronic diseases who were high users of hospital resources were assigned community health workers to help coordinate their care. The workers were trained and employed by the University of New Mexico. These plan members experienced significantly larger reductions in hospital admissions and prescriptions compared to similar members who received no such outreach. The resulting cost savings far exceeded the cost to run the program, according to a 2011 journal article.

“And the satisfaction coming from the members who were working with the community health workers was really high,” said Karen Warren, Molina’s vice-president of clinical operations and healthcare services. After the pilot, Molina expanded the program and began hiring community health workers directly. It sent them and some of their supervisors to the University of New Mexico for training.

But it was a bumpy transition.

“In the first few months of launching the program, some of the supervisors, especially the nursing staff, didn’t know how to work with the community health workers,” said Warren. The supervisors kept them in the office, instructing them to try and conduct health risk assessments of plan members by phone.

Warren said Molina administrators quickly saw the problem and retrained some supervisors, reassigned others and enforced the notion that community health workers “may come into the office to drop off some information or to come to a meeting, but they are based in the community,” ideally engaging with members in their homes. In some Molina health plans, community health workers have advanced to be supervisors.

But problems remain at other health plans and hospital systems, say experts. For example, some are turning their community health workers into medical or nursing assistants.

“Advocates in the field see this as a canary-in-the-coal mine kind of situation,” said Carl Rush of the Project on CHW Policy & Practice at the University of Texas Institute for Health Policy. “To community health workers, by and large, their work is a calling, a way to serve their community, and they don’t really want to be doing needle sticks and stuff like that.”

Others complain that supervisors are “limiting them and isolating them to one role,” said Sergio Matos, the co-founder and executive director of the Community Health Worker Network of New York City, which conducts research and advocates for and trains community health workers across the state. For example, some are being told that their job is solely to bring in patients and that others, such as social workers, will then do the health education and goal setting, he said.

“If you function that way, then you’re just providing disconnected, fragmented, dysfunctional services instead of a connected, strategized and resourced effort to create change in people,” said Matos.

In addition, Matos is concerned that people may view community health workers employed directly by hospitals and health plans with suspicion, as an authority figure much like a physician. “People may think, ‘Hey, you’re just here to make sure I take my medication’” and not to help with other challenges that can impact health, such as employment or housing, he said.

In an attempt to deal with the dilemma, some health care providers in the state avoid directly hiring community health workers and instead contract with community-based

organizations, and New York has become a laboratory for such experimentation, said Matos.

So have other states, said Rush. For example, health care providers in San Antonio will contract with the Martinez Street Women’s Center, a community-based neighborhood organization that employs community health workers, and “they’ll say, ‘We’ll give you the money. These are the results we want, and you figure out how to make it work based on your knowledge of the community,’ ” said Rush.

The same occurs at CREA Results, a grassroots organization in Denver, Colorado with more than 25 community health workers. CREA tells Medicaid health plans that want its help with enrollment outreach and new member education that any such campaign will not carry the health plan’s brand and must create benefits for the community beyond helping the plan meet its numbers, according to Rush.

Hospitals and health plans should contract with community-based organizations as a matter of equity, said Maria Lemus, executive director of Visión y Compromiso, a California-based organization that advocates, trains and supports community health workers and promotores. (Promotores “share the same language, culture, ethnicity, status and experiences of their communities,” according to the group’s website, as do many but not all community health workers.)

Many promotores and community health workers are volunteers, and it’s not fair to have hospital- or plan-employed workers making $35,000 a year while others do the same type of work for free, said Lemus.

“Health care organizations should be supporting community organizations so that they can pay promotores,” she said.

But that kind of cooperation is not always easy to arrange. “There are some areas in California, especially in rural areas, that don’t have community-based organizations that can take on that capacity,” said Lemus. So Visión y Compromiso is training community leaders as promotores and helping community organizations build their infrastructure so they can engage with medical providers.

DEBATING CERTIFICATION

As community health workers are increasingly seen as a critical part of health care, employers will expect that the people they hire will have a some kind of core training, a set of key competencies and a scope of practice, said Geoff Wilkinson, a clinical associate professor at Boston University School of Social Work.

“And all that drives an expectation of credentialing,” he said.

Wilkinson has been instrumental in developing Massachusetts’ certification program, which is expected to take effect in the fall and is supported by the majority of the state’s community health workers, who were deeply involved in the process.

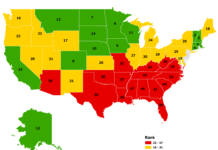

In 2002, Texas became the first state to adopt a certification program for community health workers, and Ohio soon followed. More recently, Florida, New Mexico, Oregon and Rhode Island have embraced certification, which varies from state to state but usually includes an application, references and some combination of work experience and training in core competencies, such as effective communication, client assessment and advocacy. Many other states are considering it.

But critics say state certification creates too many hurdles.

“It would eliminate a lot of community promotores from participating. It would set up criteria that may or may not be relevant,” said Lemus.

In Texas, for example, at least 21 of the 39 training programs listed on the Department of Health’s website are in English only. Florida’s certification program requires an exam. Ohio training programs must include coursework in anatomy and physiology, and applicants must have a high school degree. Most states require application fees. And all require criminal background checks.

“Nothing’s broken. Why do we need to impose certification?” asked Matos. “There’s an incredible body of knowledge out there and evidence around the effectiveness and value of community health workers, in all kinds of settings, and that’s all been done without certification.”

Several states have tried to minimize barriers. For example, the certification application in Texas has no fee, and, in recognition that many undocumented immigrants are doing this work, the state does not ask for social security numbers. Texas also exempts experienced community health workers from the training requirement in perpetuity, while Massachusetts will do so for the program’s first several years.

Wilkinson said Massachusetts has tried hard to learn from other state’s mistakes. It’s certification program will not require a high school diploma. And it will allow applicants to look back 10 years to fulfill the work experience requirement. That’s because accruing experience can take a community health worker a long time; most are funded by grants that eventually end, leading to periods of no or part-time employment.

In addition, Massachusetts’ certification board will look at each applicant’s criminal background check case by case to ensure that qualified non-violent offenders are not eliminated. A non-violent drug offender, for instance, may be uniquely qualified to work with people struggling with addiction.

But Jamie Berberena, a New Bedford, Massachusetts community health worker who is in favor of certification, is concerned that, despite the precautions, some good people may nevertheless be excluded.

“I know that the board will review case by case, but a community health worker with a criminal background might not want to revisit their past and so may opt out of certification,” said Berberena, who works for the local health department and trains community health workers to act as intermediaries between clinicians and the community.

In all states, certification is voluntary, which means employers can continue to hire community health workers who choose not to or are unable to become certified. (In Texas, the law says all CHWs must be certified, but the state does not enforce this provision.) But Matos said these programs are voluntary in name only because “the health care industry loves their certifications and titles and status and accreditations and boards” and will gravitate to community health workers who are certified.

“If there are folks who are certified, we certainly look at that. We appreciate any extra schooling or education that they have,” said Warren of Molina Healthcare. At the same time, “a fantastic set of work experiences” would be looked at in a similar way as certification, she said and added that Molina hires community health workers without certification in states that offer it.

Ultimately, community health workers who favor certification are hoping it will lead to better and more stable pay. But there is no evidence to date from the states with certification to support that notion. Grants remain the main source of funding.

Wilkinson blamed fee-for-service. Until a few years ago, Medicaid would not reimburse for community health workers because they are not licensed clinical providers. A 2014 Medicaid rule change allowed for payment for nonclinical services, but few states and few providers have taken advantage of it.

As the health care system moves away from fee-for-service to alternative payment schemes that force providers to assume more risk for the health of their covered populations, the value of community health workers will become increasingly evident, said Wilkinson. Pay should improve and come out of providers’ global budgets, he said, and some providers will want certification to help justify that.

New York is not considering statewide certification at this time, according to a health department spokesperson, but Gallego wishes it were, in case he ever had to move and apply for a new job, he said.

“For some people, it doesn’t matter that you have been doing this work for 15 years to build trust and help people if you don’t have a paper saying you are a community health worker,” said Gallego.

As the lunch break ended and workers headed to the fields, Gallego turned his van, which he calls the “confessionary,” back to the clinic. The farmworkers in the area, who are mostly single men, “know that whatever they tell me, I won’t tell anybody else, just the doctor if they give me permission,” said Gallego. “Everything said here is private. Nobody has to know.”